This week’s “Why’s this so good?” post looked at Brady Dennis’ 296-word story about a toll booth operator’s love for the wife he lost to cancer. The piece ran in 2005 as part of the St. Petersburg Times’ occasional series “300 words.” Dennis has since moved on to The Washington Post, where he is an national economics reporter (and was a Pulitzer finalist in 2009), but in a note written earlier this month, he reminisced about how the series – and the toll booth operator’s story – came about.

At the time, Chris Zuppa and I already had published about 10 pieces in the “300 Words” series. A few had turned out half decent, but almost all of them had been the product of happenstance. We’d started with a story about the security guard in our own office building, of all places. From there, we often just roamed the streets, looking for other overlooked scenes that might make for a nice picture and an interesting tale. We attended the lonely burial of an indigent man in a potter’s field. We found a pair of teenagers waiting in the Greyhound station, experiencing the wonders of first love and the open road. We found a young man on a tractor in Pahokee, cultivating the sugar fields but longing for city life.

Chris and I spent spent an hour one day writing down situations we wanted to witness or types of people we wanted to encounter. Then we set out to make that happen in a way that still left plenty of room for serendipity.

We wanted to know what it was like for a comedian to bomb, so we hung out at a comedy club until one did, and then followed him to the parking lot. We wanted to document a birth, and although it took months to find a couple and a hospital willing to trust us, it became one of my prouder moments to write about something so common and yet so intimate. We wanted to see a prison visit, and after convincing the Hillsborough County jail to let us in, we bounced from room to room until we saw a little girl. We wanted to explore a prom night, so I trolled the parking lot of Lakewood High School until I bumped into Josh King.

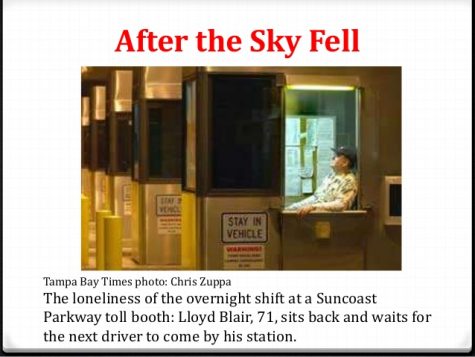

On that pad with the other ideas, I had scribbled down “toll booth operator.” That also took more work than I’d anticipated, because it turns out that the authorities frown on reporters parking their cars on the shoulder and dashing across three lanes of traffic to talk to toll collectors. During my time covering Pasco County, I had gotten to know Joanne Hurley, a spokeswoman for the Suncoast Parkway. I’m not sure she ever grasped why Chris and I wanted to come hang out with toll collectors, but eventually she agreed to meet us at a toll plaza just north of the county line for a couple hours one evening.

I remember that two toll collectors were on duty that night. I talked to the woman first, and she seemed bored and tired with the job. That weariness and the prospect of a long night ahead in her tiny booth could have made for a decent story, I thought.

Then I met Lloyd, who by comparison seemed both upbeat and serene. It struck me how he maintained such an outlook in a job that seemed pretty tedious and more than a little isolating, given the endless, brief encounters with drivers who see your toll booth as just another obstacle between them and home.

I introduced myself to Lloyd and asked him the first questions that came to mind: How did you wind up here? What did you do before this? What about before that? Soon enough, he was talking about Millie, his wife who had died of cancer. I’m sure I asked some other questions, but mostly I just listened. The story of their life together came pouring out of him – the way they met at a party in queens, their life on Staten Island and their years commuting into Manhattan, their dream of a Florida retirement, his slow realization that she would not live to share it with him. He paused only to make change for a handful of drivers passing through. At some point I asked him what Millie looked like. That’s when he whipped out her picture from his shirt pocket and said he always carried it with him. We probably talked for half an hour, 45 minutes at most. I wished him well and left him there with Chris in his solitary booth.

Because “300 Words” was sort of a side project, I didn’t go back to my notes for a week or so. One afternoon, I was supposed to speak to a small class of journalism students at USF-St. Pete about writing with brevity. I thought it would be cool if I took a rough, unpublished story to read as a way of talking through the reporting and writing process and letting them critique it and offer suggestions. I only had about an hour, so I grabbed my notes from the evening with Lloyd and started typing. I went back to my original question to him, figuring it would be the first thing anyone might wonder about a toll collector: Why are you here? And then I just tried to answer it: “Well, here’s why…” I tried to let the story unfold on paper the way it had poured out of Lloyd. It took all of 15 minutes to write (unlike my usual process of agonizing and rewriting half a dozen times). It ran in the paper virtually unchanged. And, of course, Chris took a very moving photo that said everything in a single frame.

That’s basically it. The story certainly struck a chord. To this day, I’m not quite sure why, except perhaps that all of us have been touched by love and loss, or at least can imagine ourselves in Lloyd’s shoes. The evening with Lloyd, as with almost every time we set out to do a piece for that series, underscored for me that unexpected tales come from the most unlikely (and sometimes most obvious) places, that as Don Murray said (and Tom French has reminded me), “we swim in an ocean of stories.” Sometimes it’s worthwhile to just toss the net into the water and see what rises to the surface.

It’s embarrassing that my explanation for a story has run much longer than the story itself, so I’ll shut up now. Just a brief postscript: A few years back, I was down in Florida visiting friends and drove up the Suncoast Parkway to visit a former editor in Pasco. I stopped at the toll booth, grabbed a dollar from my wallet and went to pay. There was Lloyd, smiling. “Have a great day!” he said. He didn’t recognize me in the slightest. “You too, Lloyd,” I said, and kept on driving.

Thanks to Ben Montgomery for asking Dennis to comment on the background for this story. For more on “After the sky fell.” read Montgomery’s take on how and why the story works.